South Korea’s Ballot Battlefield

- Johnson Odakkal

- Jun 26, 2025

- 7 min read

Another Episode of “Global Canvas” by JOI

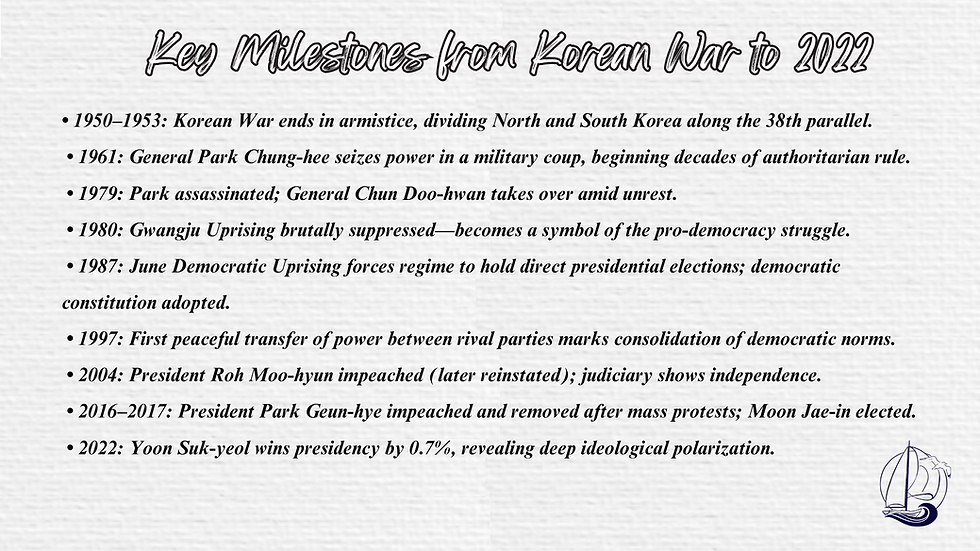

South Korea’s democracy was not born overnight, it was forged through war, authoritarianism, and a relentless struggle for freedom. From the ashes of the Korean War to decades of military rule under strongmen like Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan, it took the massive June Democratic Uprising of 1987 to force a constitutional turning point and usher in a new era of civilian rule. Since then, South Korea has built strong democratic institutions, an independent judiciary, and a vibrant civil society. Yet, beneath this progress, the legacy of authoritarianism lingers.

In recent years, Seoul’s electoral arena has become one of Asia’s most closely watched democratic theatres. From the recent razor-thin election of President Yoon Suk-yeol to the shocking imposition of martial law and the public’s swift, defiant response, the country has faced a profound test. At its heart, the crisis from 2022 to 2025 isn’t just about leadership, it’s about whether democratic institutions can withstand the weight of political ambition, or whether their survival still depends on citizens willing to rise in their defense.

Context and Background

South Korea transitioned from military dictatorship to democracy in 1987. Since then, it has held competitive elections, developed robust institutions, and maintained political stability albeit under the shadow of a powerful military, a volatile North, and a polarized electorate.

In 2022, Yoon Suk-yeol, a conservative former prosecutor with no political experience, narrowly defeated DPK’s Lee Jae-myung by just 0.7% to become president. Running on a platform of anti-corruption and tougher North Korea policies, Yoon aligned closely with Washington and Tokyo, distancing Seoul from Beijing. Domestically, his investigations into Moon Jae-in’s administration sparked accusations of political retaliation.

In the April 2024 legislative elections, Yoon’s People Power Party (PPP) suffered a major defeat, losing legislative control to the DPK and progressives. Facing mass protests, plummeting approval ratings, and an oppositional parliament, Yoon’s administration hinted at “extraordinary measures.” Leaked documents revealed discussions of emergency powers or martial law in the event of civil unrest or North Korean threats.

On December 3, 2024, Yoon declared nationwide martial law in a late-night broadcast, citing threats from “pro-North Korean forces.” Troops were deployed to the National Assembly, and restrictions on speech, assembly, and political activity were imposed. But within hours, citizens took to the streets. Lawmakers defied the crackdown, voting 190–0 to revoke the decree. Martial law was lifted by dawn. The backlash was swift: cabinet resignations followed, investigations began, and on December 14, a successful impeachment motion suspended Yoon’s powers, elevating Prime Minister Han Duck-Soo as acting president.

A snap presidential election was held on June 3, 2025. Lee Jae-myung (DPK), Han Dong-hoon (PPP), and Sim Sang-jung (Justice Party) contested the race. Lee’s decisive victory marked a liberal comeback and a renewed push for democratic reform.

Key Players and Stakeholders

People Power Party (PPP). The People Power Party is South Korea’s leading conservative force, closely aligned with President Yoon Suk-yeol since his election in 2022. The party is known for its tough stance on North Korea, firm pro-U.S. foreign policy, and a strong emphasis on law and order. Throughout Yoon’s presidency, the PPP supported his initiatives and agenda. However, the declaration of martial law in December 2024 exposed significant internal fractures. Eighteen lawmakers broke with the party line to back Yoon’s impeachment, and party leader Han Dong-hoon resigned in the wake of mounting public and political pressure.

Democratic Party of Korea (DPK). The Democratic Party of Korea is South Korea’s main liberal party and was previously in power under President Moon Jae-in. After narrowly losing the 2022 election, the DPK regained momentum following the martial law crisis. The party framed itself as a defender of democratic values, civil liberties, and balanced diplomacy. Its leader, Lee Jae-myung, emerged as a central figure in the opposition movement, organizing mass protests and steering the impeachment campaign. The DPK’s return to leadership in the 2025 re-election marks a public shift toward restoring democratic accountability.

Civil Society and Youth Movements. South Korea’s civil society, especially its youth, played a vital role in opposing the authoritarian turn during Yoon’s presidency. Immediately after the martial law declaration, citizens organized candlelight vigils, light-stick demonstrations, and public rallies across the country. Protestors often blended cultural expression with political resistance. Young people, particularly women and Gen-Z activists, used social media and creative protest strategies to challenge the government and support institutional checks. Their activism was instrumental in influencing legislators and the Constitutional Court, ultimately playing a key role in defending South Korea’s democracy.

Major Concerns and Consequences

South Korea’s recent political crisis has exposed troubling cracks in its democratic foundations. The sudden imposition of martial law marked a sharp deviation from constitutional norms and reignited fears of authoritarian regression. For a country often celebrated as a model democracy in Asia, this moment highlighted how vulnerable institutions can become when executive power overreaches. The move shook public trust and raised urgent questions about the strength of legal safeguards in times of crisis.

The consequences extended beyond domestic politics. As a key player in the Indo-Pacific, instability in Seoul threatens regional security dynamics. It complicates coordination with allies like the United States and Japan, weakens deterrence against North Korea, and risks diminishing South Korea’s credibility as a strategic partner. In a tense geopolitical environment, internal unrest undermines Seoul’s global standing.

Socially, the crisis has deepened divisions. Political polarization between conservatives and progressives has sharpened, while generational and regional gaps continue to widen. Youth and older voters appear to inhabit separate political realities, straining national unity. Rebuilding trust in institutions and restoring civic cohesion will be essential for South Korea’s democratic future.

Theoretically Speaking : Strategic Alignments and Power Shifts

Liberal Institutionalism emphasizes the central role of democratic institutions, legal norms, and international cooperation in maintaining both domestic stability and global order. In the case of South Korea, actions that undermine the rule of law or bypass constitutional procedures for political gain risk weakening the foundations of democratic governance. This not only destabilizes internal politics but also damages South Korea’s credibility and reliability as a partner within international frameworks, particularly with allies like the United States and Japan.

Constructivism focuses on how national identity, shared norms, and collective perceptions shape international behavior. South Korea has spent decades building a democratic identity rooted in civilian rule, human rights, and peaceful protest. This identity has been key to its soft power and legitimacy on the global stage. However, authoritarian tendencies and the use of emergency powers challenge these deeply held norms and could alter how South Korea is perceived both by its own citizens and by the international community.

Takeaways

South Korea’s crisis underscores that elections are not just about parties, they define how a nation wields power, upholds dissent, and positions itself globally. The case challenges assumptions about democracy’s durability in developed nations and reminds us that institutions, while essential, ultimately depend on the will of the people to defend them.

Compiled by Commodore (Dr) Johnson Odakkal (with support from Ms Vivaksha Vats)

Stay Tuned for More!

South Korea’s recent political upheaval is more than a domestic drama, it’s a critical case study in how democracies respond under pressure. From razor-thin elections to a shock martial law declaration, the nation's institutions were tested, but ultimately, its citizens rose to the occasion. The message is clear: democracy endures not just through constitutions, but through collective civic will.

In our next episode of Global Canvas, we’ll explore another region where politics and pressure collide. Until then, we’d love to hear from you.

What global shifts are keeping you up at night? Share your views in the comments or connect with us at www.johnsonodakkal.com or email ceo@johnsonodakkal.com to stay engaged.

References and Sources

Atlantic Council Experts. (2025, June 3). Experts react: What does South Korean President Lee Jae-myung mean for Indo-Pacific security?. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/experts-react/what-does-president-lee-jae-myung-mean-for-south-koreas-future/

Cha, V., & Lim, A. (2025, June 3). South Korea’s New President: Frying Pan to Fire. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

https://www.csis.org/analysis/south-koreas-new-president-frying-pan-fire

Atlantic Council Experts. (2024, December 17). The global ripple effects of South Korea’s political turmoil. Atlantic Council.

AP. (2025, June 4). South Korea has endured 6 months of political turmoil. What can we expect in Lee’s presidency?. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/rest-of-world/south-korea-has-endured-6-months-of-political-turmoil-what-can-we-expect-in-lees-presidency/articleshow/121619913.cms

How polarization undermines democracy in South Korea. (n.d.). Council of Councils. https://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global-memos/how-polarization-undermines-democracy-south-korea

Gong, S. E. (2025, June 3). South Korea elects liberal Lee Jae-myung after months of political turmoil. NPR.

https://www.npr.org/2025/06/02/g-s1-70029/south-korea-presidential-elections

South Korea election results 2025: Who won, who lost, what’s next? Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/6/3/south-korea-election-results-2025-who-won-who-lost-whats-next

Lee, J., & Park, J. (2025, June 3). Liberal Lee Jae-myung projected to win South Korea presidency in martial law “judgement day.” Reuters.

Yeung, J., Seo, Y., Bae, G., Valerio, M., & Kent, L. (2025, June 3). South Korea’s opposition leader Lee wins election as voters punish conservatives after martial law chaos. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/06/03/asia/south-korea-presidential-election-results-intl-hnk

AP. (2025, June 4). South Koreans vote for new President in wake of Yoon’s ouster over martial law. The Hindu.

Langel Tunchinmang. (2024, 24 December). From martial law to impeachment: Outcome and implications for South Korea. Indian Council of World Affairs (Government of India). https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=12173&lid=7419

Lim, A., Ji, S., & Cha, V. (2024, December 3). Yoon Declares Martial Law in South Korea. Csis.org.

https://www.csis.org/analysis/yoon-declares-martial-law-south-korea

Da-gyum, J. (2024, December 3). Full text of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s emergency martial law declaration. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/article/10012293

Tong-Hyung, K. (2025, January 15). A look at the events that led up to the arrest of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol. AP News.

Kakoti, A,R. (2024, December 27). Martial law in South Korea: A critical analysis of its political and cultural impact. Hindustan Times.

Davies, C., & Jung-a, S. (2025, April 6). “In for a rough ride”: removal of South Korea’s president leaves deep divides. Financial Times.

https://www.ft.com/content/546c9b86-c18c-4cf2-9ef6-906f1b9caa1e

Roy, T. (2024, December 7). In South Korea, a brief return to martial law and the spirit of protest that reversed it. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/south-korea-martial-law-protest-spirit-9711502/

Comments